Section 1: The Strategic Imperative: The Reign of the “Silent Global Admin”

1.1. Executive Summary: The Critical Flaw in Modern Cloud Identity Security

The vast majority of modern cloud identity architectures contain a critical, self-inflicted flaw: Standing Privileged Access (SPA). This flaw is epitomized by the organizational practice of maintaining “Silent Global Admin” accounts—overly permissive identities granted permanent, 24/7 high-level rights for day-to-day operational work. The existence of these standing assignments transforms any low-level compromise, such as a successful phishing attempt or malware infection, into a full-scale corporate catastrophe. Statistical evidence confirms that privileged credentials are the primary target: a staggering 74% of breaches involve the abuse of privileged credentials. This establishes Standing Privileged Access as the single largest preventable security risk within the enterprise.

To mitigate this pervasive threat, the immediate strategic directive must be the elimination of all SPA. This requires mandating a Zero Standing Privilege (ZSP) architecture, which is only achievable through the implementation of automated, policy-driven Just-in-Time (JIT) controls, managed by a robust Privileged Identity Management (PIM) solution. This strategic shift moves the security posture from detection-based defense, which has proven unreliable at the highest privilege levels, to preventative control.

1.2. The Definition and Danger of Standing Privileged Access (SPA)

Standing Privileged Access is defined as any highly-privileged account—such as a Global Administrator, Domain Administrator, or Subscription Owner—that retains permanent, active rights, irrespective of whether the administrator is currently executing a high-privilege task. This practice is inherently risky because it introduces unnecessary exposure. The core problem is compounded by a phenomenon known as “privilege creep.” As administrative users change roles, projects conclude, or departments reorganize, their accumulated access rights often remain active. This natural process results in unmonitored privilege escalation. This accumulation transforms a simple compromised credential into a powerful vector that allows an adversary to move laterally across the network and execute devastating threats, including ransomware deployment and supply chain attacks.

The risk is not theoretical; it is driven by the human element, which is involved in 60% of all breaches. Human involvement encompasses error (such as misconfiguration), privilege misuse, or the use of stolen credentials. The simple mistake of leaving an unattended, permanently privileged session open, or falling victim to a phishing campaign while logged into a Global Admin account, amplifies the consequence of these inevitable human failures into a maximum impact event. Without dynamic controls, the standing privilege acts as a persistent key to the enterprise’s most valuable assets.

1.3. Quantifying the Cost of Credential Abuse (The Economic Fallout)

The financial exposure created by SPA is severe and quantifiable. The global average cost of a data breach is approximately $4.44 million, based on 2025 reporting. This figure dramatically increases in heavily regulated industries, such as healthcare, where the average breach cost crossed $9.77 million in 2024, maintaining its position as the most costly industry for fourteen consecutive years.

However, the average cost does not capture the true risk of privileged credential abuse. Breaches involving stolen credentials introduce extreme operational delays, taking the longest time to identify and contain, averaging 292 days. Nearly ten months of undetected access allows malicious actors extensive time to execute their objectives, leading to maximal damage. Organizations that manage to identify and resolve a breach within 200 days typically save 23% in resolution costs, underscoring the critical nature of rapid detection and containment.

Furthermore, the prevalence of privileged access is a direct driver of the most expensive attack types. Ransomware, which often relies on achieving administrative privileges to encrypt data across the network, costs organizations an average of $5.08 million per incident, and this figure specifically excludes the actual ransom payments, which can run into the tens of millions of dollars. The compounding risk, where prolonged dwell time meets maximal privilege, suggests that exposure is closer to the costs associated with a mega-breach involving 50 to 60 million records, which averaged $375 million in 2024.

Table 1: Financial and Operational Impact of Privileged Credential Compromise

| Metric | Data Insight | Source Context |

| Average Cost per Data Breach (Global) | $4.44 million (2025 avg.) | Cost surges to over $10.22 million in the US due to regulatory fines. |

| Privileged Access Involvement | 74% of breaches involve privileged credential abuse. | Confirms privileged paths are the leading attack vector. |

| Time to Identify and Contain (Credential Theft) | Averaged 292 days. | Nearly 10 months of undetected access, severely escalating damage. |

| Human Element Involvement | 60% of all breaches. | Includes error, privilege misuse, and stolen credentials. |

1.4. The Unique Threat Profile of the Cloud Global Administrator Role

The Global Administrator account is the ultimate “crown jewel” of the cloud identity infrastructure, particularly in Microsoft Entra ID (formerly Azure Active Directory). Compromise of this single account grants the attacker control over authentication for nearly all core services, including Exchange Online, SharePoint Online, and connected Azure subscriptions.

Attackers use various vectors to target this role. In hybrid environments, they may leverage federated trust relationships. For instance, if a Security Assertions Markup Language (SAML) token-signing certificate is compromised, an attacker can impersonate any user in the cloud. Alternatively, synchronization attacks can be used to modify privileged users or groups that possess administrative privileges within Microsoft 365.

The potential severity of a compromise is exemplified by high-impact vulnerabilities. A critical token-validation vulnerability in Entra ID (CVE-2025-55241) was assigned the maximum CVSS score of 10.0. This flaw demonstrated that token validation failures could allow attackers to impersonate any user, including Global Administrators, resulting in cross-tenant privilege escalation and full tenant compromise. The profound implication of this and similar attacks is that unauthorized access is not merely possible, but catastrophic, giving an attacker the power to create accounts, grant permissions, exfiltrate user and configuration data, and gain control of any dependent service. These risks far outweigh the negligible productivity gains afforded by standing access.

Section 2: Architectural Foundations: Zero Trust and the Principle of Least Privilege (POLP)

2.1. Transitioning from Perimeter Defense to Zero Trust Architecture

Traditional network security relies on a perimeter defense model, often described as a “castle-and-moat.” If an entity is inside the perimeter, it is implicitly trusted. However, with the evolution of cloud services, supply chain threats, and sophisticated bad actors, this model is no longer viable. Organizations must transition to a Zero Trust security strategy, which operates on the principle that trust is never granted implicitly, regardless of the user’s location or the network they originate from.

In a Zero Trust framework, access to resources must be continuously verified. This approach fundamentally shifts the focus of security from the network boundary to the identity itself. For instance, in a traditional model, having the “key” to the front door (a valid credential) grants access to all rooms and cabinets; in a Zero Trust framework, that key only grants entry through the front door, and continuous, positive identity assurance is required to gain access to individual resources and systems. This model mandates that all security controls center around the core tenet of identity governance.

2.2. The Mandate of POLP: Limiting Scope, Time, and Context

The operational bedrock of Zero Trust is the Principle of Least Privilege (POLP). POLP is a computer security concept requiring that users, applications, or systems be granted only the minimum necessary access rights—no more, no less—to perform a specific task. POLP is universally recognized as one of the most effective practices for strengthening an organization’s overall cybersecurity posture.

Effective implementation of POLP requires controlling three critical dimensions of privilege:

- Scope (Just Enough Access – JEA): Access must be limited to the specific resource set required. For cloud environments, this means granting a role only at the resource group or resource level, rather than at the broader subscription or management group level. This fine-grained control prevents unauthorized control of mission-critical systems and limits the lateral movement an attacker can execute if the credential is compromised.

- Time (Just-in-Time – JIT): Privilege must be temporary and automatically revoked upon completion of the task. This is the necessary mechanism to eliminate SPA.

- Context: High-assurance security controls, such as Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) and device compliance, must be required before any privilege elevation is permitted.

When these dimensions are not strictly controlled, users accumulate elevated privileges over time, a state known as privilege creep. This results in unmonitored privilege escalation, substantially increasing organizational vulnerability.

2.3. Defining Zero Standing Privilege (ZSP) and its Role in Cloud Identity

Zero Standing Privilege (ZSP), sometimes referred to as Zero Standing Access (ZSA), is the rigorous operationalization of the Principle of Least Privilege. ZSP mandates that all permanent administrative assignments are eliminated, making all privileged access conditional, temporary, and subject to request/approval workflows.

ZSP is critical for cloud identity security because it proactively eliminates the attack surface presented by constantly active high-privilege accounts. The continuous nature of ZSP directly addresses several organizational hurdles, including the difficulties posed by Shadow IT—where users employ illicit software or platforms. These unauthorized access points can sabotage ZSP initiatives by introducing vulnerabilities outside the control of the security team. By mandating ZSP, organizations reduce the likelihood that unknown or unsanctioned access points can be exploited.

The transition to ZSP is not a one-time configuration but a continuous journey. Cloud administrators and developers must continuously set, verify, and refine permissions over time, creating a feedback loop of improvement that ensures privileges remain relevant and minimal.

2.4. Architectural Strategies for Delegation: Moving Beyond Global Admin

Achieving ZSP requires a complete overhaul of privileged access delegation, moving away from relying on the highly permissive Global Administrator (GA) role for daily operations. Organizational best practice recommends limiting the number of standing Global Administrators to fewer than five. Any administrative functions beyond essential, emergency coverage must be delegated to specialized, scoped roles.

The primary pitfall in this process is relying on static Role-Based Access Control (RBAC). While RBAC is necessary to put POLP into action by assigning access based on job function , static assignments can quickly lead to over-privileged status if not dynamically managed.

Instead, organizations must use granular, predefined cloud roles that grant only the necessary permissions for specific tasks. For instance, creating enterprise applications should be delegated to the Cloud Application Administrator role, rather than requiring GA access. Similarly, configuring access management for specific Azure resources should use a narrow scope, such as resource group or resource, instead of the broader subscription or management group. This delegation segregates duties, limits the impact of compromise, and ensures that the Global Administrator role is truly reserved for critical, tenant-wide functions.

Table 2 illustrates the necessity of this strategic delegation:

Table 2: Delegated Cloud Administrative Roles vs. Global Administrator

| Common Administrative Task | Least-Privileged Role (Entra ID Example) | Risk Reduction Justification |

| Creating Enterprise Applications | Cloud Application Administrator | Prevents modification of highly critical service principals or tenant-wide security settings. |

| Managing User Mailboxes/Settings | Exchange Administrator | Limits control to M365 email systems only, protecting core directory services. |

| Assigning Security Roles (PIM Managed) | Privileged Role Administrator | Limits the authority to grant elevated rights, maintaining governance over PIM itself. |

| Auditing Security Logs | Security Reader/Global Reader | Allows monitoring without the ability to modify or delete critical configuration. |

Section 3: Privileged Identity Management (PIM) and Just-in-Time (JIT) Access

3.1. PIM Defined: Managing the Identity Lifecycle of the Administrator

Privileged Identity Management (PIM) is a dedicated security solution specifically designed to oversee, control, and monitor the elevated access rights granted to users within the IT environment. PIM provides essential governance for access to critical resources, including sensitive files, administrative user accounts, databases, and core security systems.

PIM’s focus is distinct from general Privileged Access Management (PAM), which often manages shared credentials and access to privileged accounts. PIM centers on managing the identities with elevated access rights, emphasizing control and monitoring throughout the lifecycle of the administrator’s permissions. This service is crucial because it transforms standing access into time-based and approval-based role activation, effectively mitigating the risks associated with excessive, unnecessary, or misused access permissions.

Table 3: PIM Features Mapped to Least Privilege Security Goals

| PIM Feature/Control | Principle Enforced (POLP Aspect) | Risk Mitigation Outcome |

| Just-in-Time (JIT) Activation | Time-Bound Access | Eliminates standing access, drastically reducing the attacker’s window of opportunity. |

| MFA Enforcement on Activation | High Assurance Verification | Prevents token or password reuse from compromised session/credential dumps. |

| Role-Based Granular Authorization | Just Enough Access (JEA) | Ensures users elevate only to the specific, minimum permissions required for the task. |

| Approval Workflows | Context/Policy Enforcement | Introduces oversight that could “stop attackers in their tracks even after they’ve succeeded in compromising administrative credentials”. |

| Access Review and Auditing | Continuous Monitoring | Prevents “privilege creep” and simplifies regulatory compliance requirements. |

3.2. Deep Dive into JIT Access Models: Temporary Elevation vs. Ephemeral Accounts

Just-in-Time (JIT) access is the engineering mechanism used by PIM to enforce the temporal dimension of POLP. With JIT, permissions are granted only on a per-request basis, typically through an automated workflow. Limiting the window of time a user holds elevated rights dramatically strengthens the security posture.

There are two primary JIT models:

- Temporary Elevation (The Standard PIM Model): The user retains their existing, standard account but requests a temporary elevation to a privileged role (e.g., Global Admin). Access is granted only for a specific, pre-defined duration (e.g., one to four hours) and is automatically revoked when the duration expires.

- Ephemeral Access: A unique, temporary account is created specifically for the user’s task and is automatically deleted once the task is complete. This model eliminates the risk of lingering privileges and minimizes the potential for unauthorized access by acting as a disposable, single-use key.

Regardless of the model, JIT requires Justification-Based Access. Users must provide a meaningful and specific justification for requiring the elevation (e.g., “Applying security patch to critical database”), which is reviewed against predefined policies. This step enforces accountability and ensures that administrative tasks are performed under a clear, auditable context.

3.3. Core PIM Features for Audit and Control

PIM delivers several critical governance capabilities beyond simple time restriction:

MFA Enforcement on Activation: This is a vital security feature. While standard administrator accounts might already require MFA at login, PIM enforces MFA specifically at the moment the administrator requests role activation. This is a necessary defense against advanced token theft attacks. If an attacker manages to compromise a user’s session token—which often bypasses the initial MFA check—the attacker would still be forced to present high-assurance authentication (MFA) to activate the privileged role through PIM. This secondary, mandatory check significantly mitigates the risk of token reuse.

Approval Workflows: For highly sensitive or impactful roles, PIM can be configured to require an approval workflow, mandating that another administrator or security manager sign off before the privileges are activated. Implementing this control creates a procedural hurdle that can stop malicious actors in their tracks, even if they have already succeeded in compromising the administrative credentials, providing a critical operational air gap.

Continuous Auditing and Access Reviews: PIM simplifies compliance by providing a central location for detailed audit history, documenting precisely when roles were activated, by whom, and for how long. Furthermore, PIM enables the configuration of recurring access reviews. These reviews automatically prompt users and managers to confirm whether a user still requires eligibility for a role, automatically revoking unneeded permissions over time and providing the necessary organizational mechanism to counteract “privilege creep”.

3.4. Extending PIM Scope: Controlling Hybrid and On-Premises Privileges

The scope of PIM is not confined solely to cloud resources. A comprehensive ZSP strategy must protect the entire digital estate, including hybrid and on-premises systems. PIM solutions can control on-premises Active Directory (AD) roles and privilege groups through features such as group-based write-back.

This integration ensures that Just-in-Time principles are applied end-to-end. By setting up PIM to manage group membership, an organization can control access rights for diverse critical infrastructure, including SQL database administrator rights, VMware access, network device administrative rights (Cisco, Palo Alto), and local Windows and Linux admin rights. This capability allows IT teams to operate with virtually no permanent administrative rights on their daily accounts, ensuring that the ZSP mandate is enforced across the entire hybrid security boundary.

Section 4: The Severity of Compromise: Attack Vectors and Case Studies

4.1. Analysis of Global Admin Compromise Pathways

The pathways to Global Administrator compromise are varied but often initiated by surprisingly simple failures. While advanced techniques exist, basic credential leakage remains a major threat. Case studies reveal instances where easily discoverable hard-coded credentials or password reset tokens leaked in application responses allowed attackers to take over admin accounts with minimal effort.

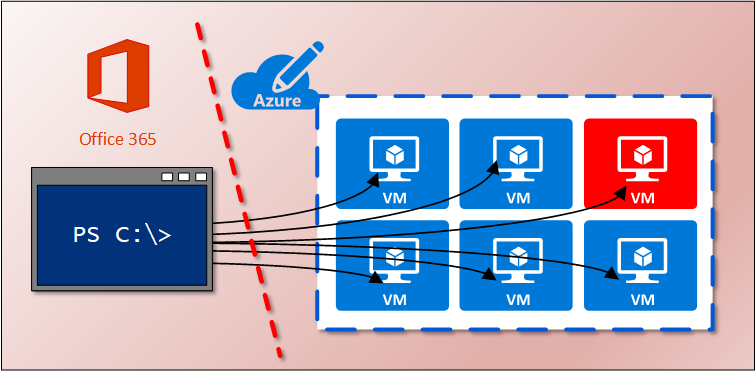

In addition to external breaches, local machine compromise is a direct precursor to identity theft. One case study detailed how an employee’s mistake—downloading unauthorized software based on an online forum recommendation—resulted in the installation of spyware. This malware stole credentials, allowing malicious actors to create unauthorized accounts and ultimately delete a key administrator’s access, escalating a minor slip into a full-scale cyber attack.

In hybrid environments, attackers target the core trust mechanisms. Compromising the Security Assertions Markup Language (SAML) token-signing certificate is a viable pathway that enables attackers to impersonate any user, including highly privileged ones, across the cloud environment.

4.2. Forensic Blind Spots: The Impact of Compromise on Logging and Auditability

A critical, often overlooked dimension of privileged account compromise is the catastrophic failure of detective controls when facing sophisticated attacks. Recent analysis highlights that when a compromised Global Administrator credential is exploited via legacy interfaces, specifically the deprecated Azure AD Graph API (graph.windows.net), the actions can bypass Multi-Factor Authentication, Conditional Access, and, most critically, API-level logging.

This logging failure creates what can be termed a “Zero Trace Attack.” An attacker impersonating a Global Administrator could make unauthorized modifications, exfiltrate sensitive user PII, group and role details, and device information without leaving any forensic trail of the intrusion. The lack of forensic evidence severely complicates post-incident investigation and containment. If the ability to audit and detect intrusion collapses at the highest level of privilege, the entire foundation of the security program is compromised, making preventative controls (ZSA) an absolute necessity.

4.3. High-Profile Vulnerabilities and Cross-Tenant Escalation Risks

The scale of the threat posed by standing Global Administrator accounts was starkly demonstrated by the critical token validation vulnerability, CVE-2025-55241. This flaw was assigned a maximum CVSS score of 10.0 and was described as a privilege escalation failure that could have allowed an attacker to compromise virtually every Entra ID tenant globally.

The vulnerability stemmed from weaknesses in service-to-service (S2S) “actor” tokens and a fatal flaw in the legacy Graph API that failed to validate the originating tenant. The practical impact of such an impersonation is severe: an attacker gains the ability to create new accounts, grant themselves additional persistent permissions, and seize control of any service relying on Entra ID for authentication, such as SharePoint Online and Exchange Online, resulting in full tenant compromise.

The existence of such high-impact flaws underscores that technical controls alone are insufficient if standing access is present. The only way to neutralize the threat is to ensure that the privilege—the potential point of exploitation—does not exist permanently.

4.4. The Role of the Human Element: Error, Social Engineering, and Privilege Misuse

The human element is a critical vulnerability vector. Beyond external attacks, insider error is constantly present. Statistics show that misconfiguration alone accounts for 30% of human-caused breaches. When an administrator performs a routine task while holding standing Global Administrator privileges, any mistake in configuration is immediately magnified into a tenant-wide outage or data integrity issue.

The requirement for Justification-Based Access within a PIM framework serves to mitigate both deliberate and accidental misuse. By forcing administrators to clearly state their purpose before elevation, the system reduces the risk of inadvertent actions and ensures that non-essential administrative work is never performed under maximal privilege. This procedural requirement imposes necessary governance on administrative actions, thereby limiting the opportunity for both error and privilege abuse.

Section 5: Implementation Roadmap and Change Management

5.1. Addressing the Productivity Myth: Automation and Workflow Streamlining

A significant obstacle to ZSP adoption is organizational resistance, particularly from IT staff who fear that JIT access introduces unnecessary friction, slows down critical operations, and creates cumbersome overhead. This is frequently referred to as the “productivity myth.”

However, the reality is that automated JIT access management enhances operational efficiency. Automated platforms streamline access requests and approvals based on predefined policies, eliminating the manual overhead required for servicing requests. This automation results in faster workflows, allowing employees and IT teams to quickly and easily obtain necessary privileges without manual intervention. JIT models, when properly implemented, free strategic IT personnel from playing the perpetual role of “whack-a-mole” for access demands, allowing them to focus on more strategic initiatives.

Furthermore, the centralized, policy-driven workflows inherent in PIM can yield quantifiable returns on investment. Related implementations show that streamlining data management and workflow orchestration can lead to significant productivity gains, such as a 50% reduction in time required for classification tasks. The operational efficiencies gained by replacing manual, decentralized processes with automated, policy-enforced JIT far outweigh the perceived inconvenience of elevation.

5.2. Overcoming Organizational Resistance to JIT Adoption

Successful PIM adoption requires a change management strategy focused on securing executive support and providing comprehensive staff training. The transition must be framed not as a punitive or burdensome measure targeted at security-conscious users, but as a mandatory cultural shift toward enterprise-wide Zero Trust practices.

A highly effective strategy for minimizing friction is the Normalization of JIT. Organizations should implement Just-in-Time activation for all eligible roles, not just the high-impact Global Administrator role. By extending JIT to encompass standard administrative duties, the practice becomes routine and second nature, integrating seamlessly into daily workflows. This broad implementation transforms JIT from a restrictive security imposition into a normalized, routine component of the Zero Trust culture, significantly reducing user friction and behavioral resistance.

Furthermore, complexity must be actively managed. To address real-world administrative tasks that may require multiple privileges simultaneously (e.g., both an Entra ID role and an Azure resource role), organizations should leverage PIM for Groups. This capability allows administrators to activate multiple necessary roles at once through a single request, streamlining the elevation process and maintaining operational velocity.

5.3. Step-by-Step Transition to Zero Standing Access (ZSA): Planning and Execution

The implementation of ZSA must follow a structured, phased approach to ensure business continuity and mitigate risk:

- Discovery and Inventory: The process begins with a comprehensive audit to identify all existing privileged accounts, including those that are long-forgotten, shared, or hard-coded credentials sprawled across the environment.

- Define Project Scope and Governance: Establish a cross-functional governance team involving IT, security, and legal representatives. Define clear data models and business objectives for the transition.

- Establish Break Glass Accounts: Before converting any standing GAs, establish two or three highly secured, cloud-native “Break Glass” accounts. These accounts must be assigned the Global Admin role outside of PIM and must not be synchronized from on-premises Active Directory. These accounts are the essential lifeline for tenant recovery should identity services fail due to licensing lapse or system outage, and their credentials must be secured physically and audibly.

- Implement Least Privilege Roles and Delegation: Review existing standing GA accounts. Convert or remove users who lack clear justification for administrator access. Delegate tasks to specialized, minimum-privilege roles wherever possible.

- PIM Deployment (Pilot Phase): Implement PIM and JIT policies first for non-critical administrative roles. Gradually move up the privilege hierarchy to the highly sensitive roles, such as Privileged Role Administrator and Global Administrator.

- Enforce Mandatory Controls: Require MFA enforcement specifically at the point of role activation and mandate meaningful justifications for all elevation requests to ensure necessary accountability.

5.4. Essential Governance: Access Reviews and Policy Enforcement

Successful ZSA implementation is dependent on rigorous, continuous governance controls. Point-in-time controls are insufficient for managing modern privileged access.

Continuous Monitoring: Organizations must implement sophisticated monitoring systems capable of revealing user actions and anomalous usage patterns in real-time during privileged sessions. These tools are necessary to identify potential threats or policy violations that may occur within the limited JIT window. Furthermore, continuous monitoring systems must detect and map unauthorized access points and network usage (Shadow IT), ensuring that systems outside the scope of PIM are still accounted for.

Recurring Access Reviews: PIM must be configured to schedule recurring access reviews that automatically evaluate the continued eligibility of users for all privileged roles. This automated revocation process is critical for preventing the reintroduction of “privilege creep.” Organizations should also aim to limit the total number of privileged role assignments (eligible or active) to fewer than ten across the directory. Finally, for simplified governance and scalability, best practice dictates that roles should be assigned to groups, rather than directly to individual users.

Section 6: Conclusion and Strategic Recommendations

6.1. Key Takeaways for Senior Leadership

The analysis confirms that the continued use of standing Global Administrator accounts is an unnecessary, self-imposed liability. Allowing permanent, elevated access provides attackers with a crucial window of opportunity (average 292 days of dwell time) that leads to catastrophic, multi-million dollar data breach events. Furthermore, the exposure is exponentially magnified by the existence of critical vulnerabilities that, when exploited, can bypass traditional MFA and Conditional Access, and, most alarmingly, enable actions without leaving any forensic audit trail.

The strategic solution is clear: the operational necessity of the Principle of Least Privilege (POLP) must be enforced through Zero Standing Privilege (ZSP). Privileged Identity Management (PIM) is the required engineering control to achieve ZSP, providing the necessary temporal control (JIT activation), high-assurance authentication (MFA on activation), and continuous auditability.

6.2. Prioritized Mitigation Strategies

To achieve a Zero Standing Access posture and minimize organizational liability, the following strategic steps are immediately required:

- Immediate Standing Access Remediation: The organization must immediately limit permanent Global Administrator assignments to fewer than five accounts, designated exclusively for emergency use. These standing accounts must be cloud-native, secured with multi-factor authentication, and excluded from federation where possible.

- Mandate PIM and JIT Deployment: A formal mandate must be issued to implement Privileged Identity Management (PIM) and require Just-in-Time (JIT) activation for all remaining eligible privileged roles, starting with the highest-risk roles such as the Global Administrator and Privileged Role Administrator. Approval workflows must be enforced for these high-impact elevations.

- Normalize the Culture of ZSP: The implementation plan must incorporate strategies to overcome the productivity myth by rolling out automated JIT workflows broadly across administrative roles. This normalization ensures JIT becomes a routine secure habit, reducing organizational resistance and integrating ZSP into the daily operational culture.

- Audit the Cloud Identity Foundation: Conduct an immediate, rigorous audit of all administrative activities, specifically checking for dependencies on legacy interfaces, such as the deprecated Azure AD Graph API. This audit must ensure that all privileged administrative actions are logged and monitored, thereby eliminating known forensic blind spots that allow attacks to operate without leaving critical traces.